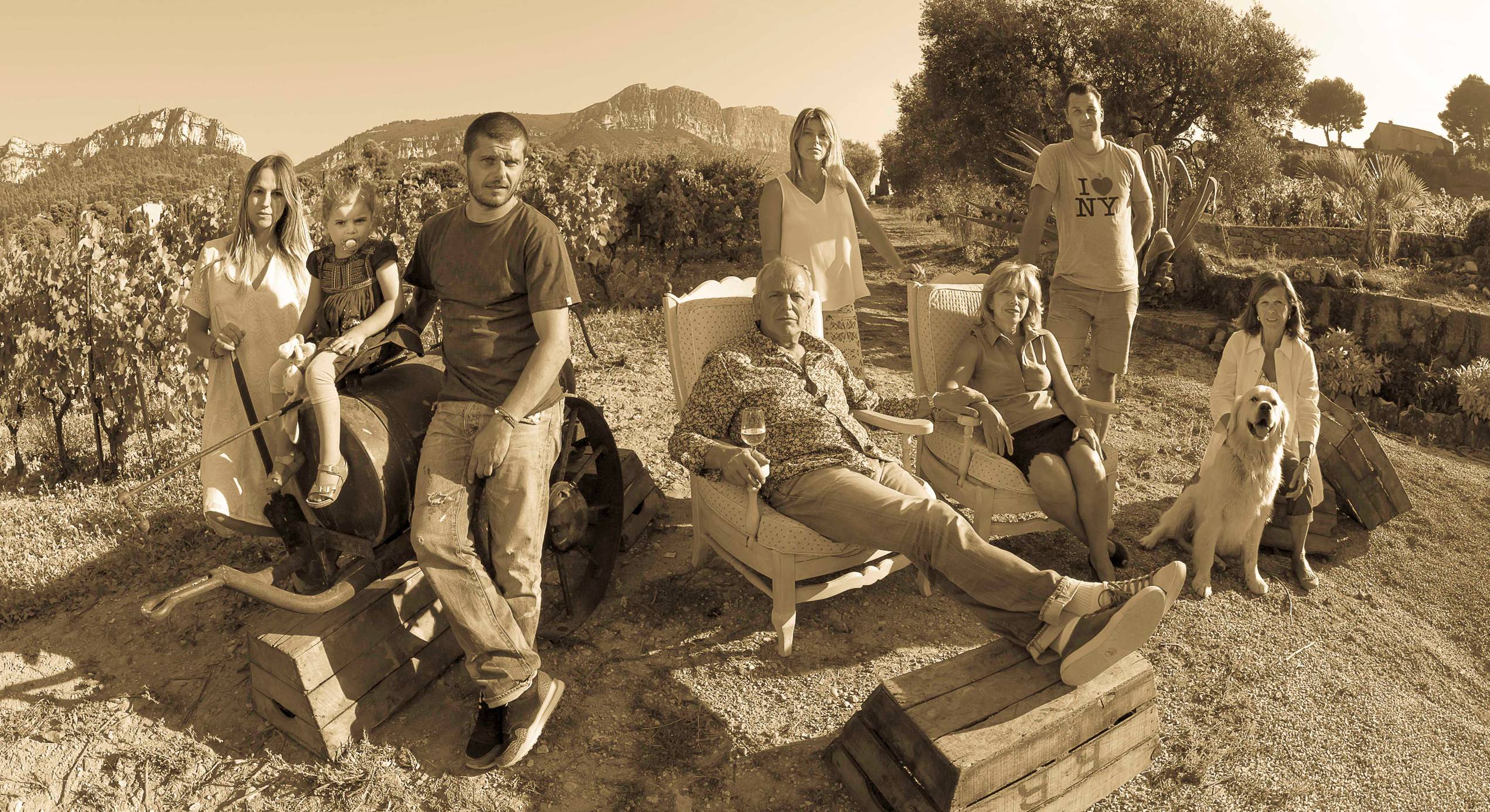

The soulful summit of Syrah

The appellations in the northern stretches of the Rhône, between Vienne and Valence, constitute the most prized terroirs for the Syrah grape variety in the world, as well as singular appellations for Viognier, and inimitable examples of the indigenous Marsanne and Roussanne. In the appellations of Côte-Rôtie, Hermitage, Saint-Joseph, and Cornas, Syrah thrives on steep, sometimes vertiginous hillsides in a variety of soils, including schist (in Côte-Rôtie in particular) and granite. And the dramatic and variously soiled slopes of Condrieu produce the rare example of Viognier which is dominated by terroir rather than varietal character. We have always sought growers here deeply informed by traditional practices: working the soil, fermenting exclusively or primarily using whole clusters, and avoiding the imprint of new oak in the aging process.