Insights

Grower Spotlights

Read more

Foreau’s Peerless Vouvray Brut: Another Side of Chenin Blanc

From their enviable holdings in the tuffeau heart of the appellation, father and son Philippe and Vincent Foreau shepherd into bottle scintillating, kaleidoscopic wines which vibrate with mineral intensity, maintaining their haunting depth and laser-like precision even at triple-digit levels of residual sugar or in the presence of bubbles.

Featured

Grower Spotlights

Introducing Domaine de la Touraize

We are thrilled to introduce Domaine de la Touraize—the eighth grower in RWM’s long history with the Jura. André-Jean (“A-J”) Morin is the eighth generation of Morin to tend the vine in Arbois, beginning with his ancestor Etienne in 1704, but the family enterprise nearly didn’t survive the calamitous 20th century.

Grower Spotlights

New Releases from Josef Fischer

Our launch earlier this year of Josef “Joe” Fischer’s ebullient wines from the Danube’s southern banks met with immediate success, and we are thrilled to expand our work with this up-and-coming Wachau superstar this fall.

Grower Spotlights

New Releases from Ficomontanino

Within Tuscany’s relatively conservative winegrowing culture, Maria Sole Gianelli’s wines are a breath of fresh air. Maria Sole’s farm is called Ficomontanino (roughly, “Little Fig Mountain”), a property her grandfather acquired in the 1960s as a place to produce olive oil and breed horses.

Grower Spotlights

Luigi Oddero’s 2016 Vignarionda: Barolo at its Most Singular

While “greatest” can be a matter of personal preference, what sets apart Vignarionda is its utter distinctiveness; it is as different in character from its immediate Serralunga neighbors as it is from sites much further away. In that regard, it embodies the essential irreducibility of a true grand cru—a site with a force of personality that overwhelms other considerations and resoundingly affirms the mysteries of terroir.

Grower Spotlights

The Beauty of Cassis Blanc: Sublime Seaside Wines from Domaine du Bagnol

Bagnol's duo of their flagship Cassis Blanc and the singular "Caganis" represents an apex expression of Mediterranean white wine, both wines displaying a combination of southerly generosity, textural complexity, and salty cut that places them well within the ranks of better-known peers in fancier appellations.

Grower Spotlights

La Torre: New Releases from RWM’s Oldest Tuscan Partnership

Brunello developed a reputation for richness and heft over the years, and while it is undoubtedly more substantial than its counterparts in Chianti and Montepulciano, traditional Brunello should still express the inherent freshness and lift of Sangiovese. Thankfully, La Torre's does so with aplomb, its character given added finesse due to La Sesta's poor soil and high altitude.

Grower Spotlights

Bramaterra’s Rising Star: Andrea Mosca of NOAH

It is precisely Mosca's kind of detailed, soil-based approach which points to an ever-brighter future for this winegrowing region which is still clawing itself out from prolonged economic depression, and we are excited to offer such unique and well-rendered lenses into this terroir.

Grower Spotlights

Gianluca Bergianti’s Terrevive: The Spearpoint of Lambrusco’s Vanguard

Gianluca produces sparkling wines which sizzle with life—electrifying, mineral-saturated bottlings that revel in their expressive power. They offer a palpable and exciting drinking experience fully at odds with mainstream Lambrusco’s conservative simplicity; for us, tasting them was like encountering the truth of the region for the first time.

Grower Spotlights

The Iconic Enfer d’Arvier from Danilo Thomain Returns

With his two hectares in production—one of which he cleared and planted himself several years ago—Danilo stands as the only independent bottler of wine in this zone whose viticultural records date back to the 13th century.

Grower Spotlights

Cappellano: the Creator of Chinato

Those who have tasted great Chinato know of its shocking complexity, and there are simply none better than Cappellano's.

Grower Spotlights

Joseph Dorbon: Retired but not Finished

Although he is now fully retired, we still have a few Joseph-made vintages to look forward to, including a forthcoming batch of new arrivals.

Grower Spotlights

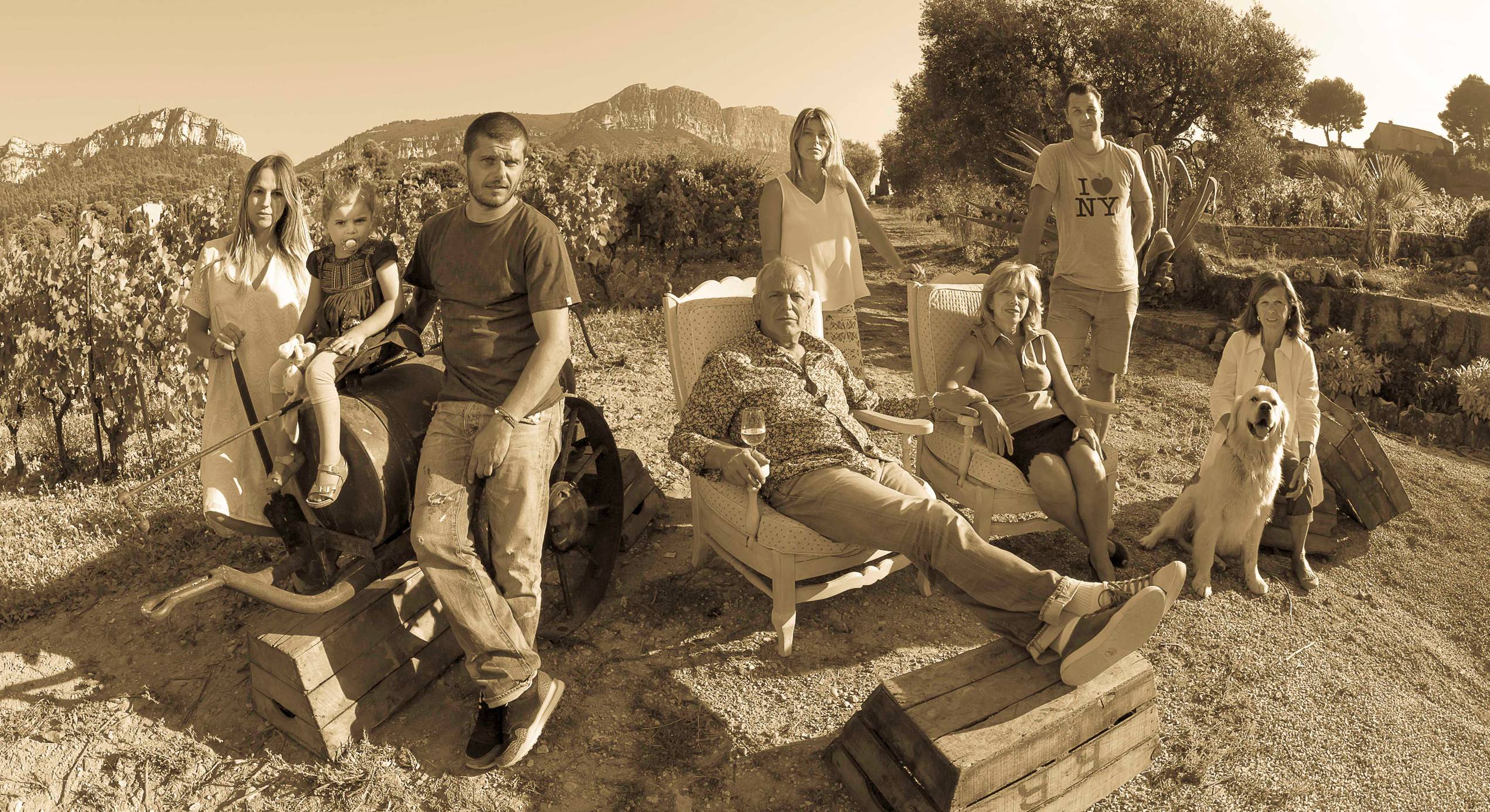

The Crown Jewel of Provence

Through our many years of partnership, we have advocated incessantly for broader recognition of the greatness of Chateau Simone. Super-famous in their homeland and gracing the list of seemingly every good restaurant in France, Simone for many years was something of an underground phenomenon in the US, known to some cognoscenti but virtually unrecognized by the larger wine-drinking public.